I wrote the first version of this story twenty-some years ago. It bounced dutifully around the semi-pro markets getting rejection letters, until I gave up and gave it away to a fanzine editor, along with some artwork. I trunked the story until I got back into writing in 2009, and started polishing it up. It gathered more rejection letters, until 2011 when I sent it in to a friend’s small-press anthology of Sff.net authors.

I think the book sold a few copies among the included authors and their friends, but no one else seems to know about the anthology. Which is a shame, because the other writers have some solid work in it.

There is virtually no meaningful paying reprint market for ‘Needle and Sword’; I have the rejection letters to prove it. I could self-publish it digitally with a nice cover – but I don’t really think of a 5200-word short story as a ‘book’ worth $.99 online.

So for now, until I decide to expand it into a Real Book, this newest version is a free read.

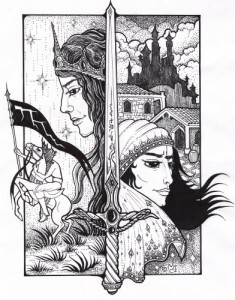

Needle and Sword, by M. Crane Hana

On the highest balcony of Kytheu Keep, Talai drew her old cutlass and leveled it against an imaginary foe. Her hand shook. Only hawks and pigeons ever saw her weep and spar with the wind in this lonely spot.

She looked south beyond the wavering blade.“Damn you, Grandfather!” she cried. “You waited too long!”

Southward, the river Kytheu dropped from blue and white peaks, twisting a serpent’s path across eighty miles of farm terraces. Behind Talai’s back, Kytheu City fanned north below its Keep: a jumble of bell towers, narrow streets, roofs tiled in coral, cream, and slate-blue. Half-hidden gardens cast squares of green shadow. Canals looped from the dock-fringed river. A merchants’ road followed the river north, where Talai never looked by choice.

After three minutes, she dropped the blade from stinging fingers. It rang and rattled on the granite tiles. Talai followed, crouching on aching knees.

“You waited too long, and I’m an old woman,” she whispered to the cutlass.

A hawk shrieked overhead.

Talai looked up, wiping tears from her stern face.

The hawk squabbled noisily with something bigger and brighter than a pigeon, then flapped off, favoring one wing.

A Channel parrot perched on the eaves, its long tail a gaudy emerald and blue banner against muted tiles. One mad pale eye glared down at her. The beak half-opened, as if to speak.

“If you’re just a parrot, you’re five hundred miles from home. If you’re not, then go away!” Talai yelled up at it.

The parrot screeched bird-laughter at her, and sidled out of view around a corner of the roof. She didn’t see it fly off.

#

“Keem, where is everyone?” Sivonie asked, closing the workroom door.

“Whacking dust out of Keep carpets,” laughed the seamstress. “Or hiding. I’d be hiding, too, but this silly quilt must ship tomorrow, a birth-gift for some big upriver family. Is that Lady Migian’s mantle?”

Sivonie unrolled a shimmering bundle. Pearl-shell spangles weighted a deep border on silver silk mesh, a design of oared ships gliding over placid currents.

“What will this one do?” asked Keem.

“If Migian’s too angry, not much. But she’ll feel prettier, wearing it. And she is, when her lips aren’t pinched in a frown. Maybe that husband of hers will see it, and say so.”

“I’ve seen Damo pieces like that down at the Guildhall museum,” said Keem, setting her own project aside. “Last time I saw this, you’d just started it. Sneaking off to that drafty old chapel again?”

“The Guildmistress gave me permission.”

“After you scrubbed the place clean, and took a white-lamp down for clear light. At least it’s quiet. No gabbling girls around to sigh over handsome squires.” The seamstress gave Sivonie a sharp look. “Any squires sighing over big green eyes?”

“I’m not meeting anyone there. It’s just peaceful. A Damo place. Helps me think.”

Damo! Sivonie breathed the word into a prayer, a plea, a thread of subtle magic.

Farmers sometimes tilled up Damo gold on the terraces, or turned over stones carved with ancient, sinuous scripts. Kytheu Keep itself sprang from a Damo foundation. Deep at its heart lay Sivonie’s ‘chapel’, a room quartered by long tables and a deep well at the center.

Rumor made the chapel an ancient torture-chamber haunted by Damo ghosts. The well breathed only cool air rich with the scent of water slowly eating stone. The half-masked statues in the corners were strange, nameless, but not cruel to Sivonie’s eyes. They held carved objects to their lips, as if breathing upon them: a smith’s hammer, a stoneworker’s caliper, a scholar’s scroll, a weaver’s drop-spindle.

“Don’t need thinking to sew,” Keem said, bending over her work again. “Do you notice anything that isn’t Damo-wrought? You found the only two carved blocks in the dormer walls, first night you were here. And remember Migian’s husband, last week?”

“Keem! I would never…”

“Of course not, girl, you were only looking at his cloak pin, the one Damo thing on him!”

“Damo work seems more real than anything else.” Tall, sturdy Sivonie glanced at the workroom mirrors. She flipped the mantle over her dark-brown braids, brought up a fold to cover her nose and mouth.

“Sivvie!” Keem hissed. “Don’t you dare leave a mark, or any long dark hairs! Lady Migian’s hair is dyed yellow as dawnlight. Want her fine husband explaining himself? Again?” Keem’s stern voice faltered into giggles.

“I’m not likely to ruin it,” said Sivonie, smiling under the sheer fabric. “Or set a quarrel between two families.Wouldn’t be fair to Migian’s husband’s maize, letting good grain rot in warehouses up south.”

“Not his grain, anymore.”

Sivonie lowered her voice. “My uncle Haptin says Migian’s folk traded ship contracts for grain and a handsome young husband. The wrong hair on a new mantle, once too often, and he’ll be sent south in disgrace. Then half of Ten-Mile Terrace’s maize rots because no barge captain wants to anger Migian’s family. The rebels don’t get grain for their horses and cookpots. No rebels, and eventually war spills downriver to us.”

Keem looked dubious. “You hear all this, sewing in the cellar?”

“I hear it at my aunt’s inn,” Sivonie said, wrapping the mantle in clean muslin. “At the docks, when my father brings another barge from the south. In the halls up here, after the councils meet. Kytheu’s restless.”

“Then why not leave? You could already teach in any town between here and the mountains, Sivvie. Why are you still paying apprentice-fees to sew quilts and pretty mantles with the rest of us?”

Sivonie shrugged. “I’m not finished learning yet. In three more years, the coin I earn from these will be mine, not the Guild’s. Then I can go find even better teachers.”

“Pity,” said Keem, patting the packet of folded muslin in Sivonie’s hands. “That mantle looked proper on you. You could always make your own.”

Sivonie shook her head, holding the muslin to her lips. “Where would I wear it? It’s just a toy. I wish I could make something important.”

“Maybe you’ll be chosen to sew honor and valor into a Queen’s coronation robes, eh?” Keem teased.

#

Haptin Firelark held court over two tables and a tiled yard, separated from the street by a low wall of pattern pierced brick. He stood on a mounting-block to see over the tables, and waved his arms toward the climax of a favorite story.

“- Parrot ruffled his green wings and squawked, ‘That was your seventh quest, Lord Linca. You may claim seven wishes from me, one for each quest.’ We know Linca wished for his Damothani sword, his golden Damothani horse, and for a long and happy life, but legend tells us nothing of his other four wishes.” Haptin bowed to less applause than he’d wanted.

Under the table, someone imitated a parrot. Haptin hoped it was a parrot, and not Maraga’s bean casserole’s revenge. “Wish I had paying listeners today,” he muttered.

“We pay,” belched Goru the Wide, sloshing his tankard in proof. “Good stories, Haptin. But we’re here for Maraga’s beer.”

“Heard better tales, recently?”

“No,” Goru admitted. “Not since I was fifteen. I remember a Damothani knight singing at the remembrances for the old Queen.”

“Is it true?” asked a barge captain in from the Delta. “Has Queen Talai sworn to crush the Isles, once she has the Commonwealth treasury behind her?”

“She’s not Queen yet,” said Goru.

“My wife’s sister’s child Sivonie studies up at the Keep,” said Haptin. “Servant‑jabber says Warlord Talai’s simmering a deal with the Damo rebels, to take that cesspool across the Channel with as little of our blood and money as can be.”

At the table below the painted lark sign, another man grunted a somber curse. “Talai’s not even Kytheu-born. And no longer much of a warrior. War? Commonwealth hasn’t fought a real battle in centuries.”

“Pardon me, master storier,” a rider interrupted from the street. “I am new to Kytheu. Perhaps you could aid me in a minor quest?”

He drawled the city-state’s name the old way, “KAI-thee-oh” instead of the modern slurred “KEE-thew”.

A Channelman, five hundred miles south of home.

Haptin noted the stranger’s sky‑blue silk tunic, grey leather trousers and soft boots, and grey cotton brocade over‑robe. A gaudy sword-hilt jutted from a worn back-scabbard. Old white scars striped the man’s tanned hands. A broad grey hat shaded his pale, angular face. His blue-green Channelfolk eyes, more iris than white, considered and dismissed Goru and the Delta captain.

The stranger’s big yellow mare nosed the grass between the pierced wall and the street cobblestones. Through the largest holes, Haptin saw that the mare’s shoes were sharpened steel. Her tack and saddle were plain olive-green leather.

From the scales on the saddle and breast‑band, Haptin thought: Delta crocodile. Tanned and worked by a master. Plain, but not cheap. That’s a warhorse, or I’m Goru’s granny. Why is a Channelman who walks like a mercenary got up as a dandy? With green glass baubles stuck to the hilt of a cheap blade?

“A quest?” Haptin asked, sponging up the stranger’s appearance.

“I’m looking for a woman,” the man began.

“Aren’t we all,” burped Goru the Wide, grin widening as he studied the stranger.

“What is her name, this lady you seek?” Haptin asked, ignoring Goru.

From a saddlebag, the stranger wrestled a heavy yellow parchment envelope wrapped in green ribbons, and sealed with an officious blob of silver-dusted black wax. Wavering script decorated the parchment. After turning the thing this way and that, the stranger looked up.

“Sivonie Firelark. I think. It could say Madam Olvera at the Blown Rose in Kaspaterre, for all I can puzzle out the magistrate’s squiggles. But I had him say the name for me thrice. He paid me five silver pieces to deliver it. This woman Sivonie works up at the Hawk’s Keep. I can’t go there without a safe-pass, and the lady’s inherited some money from some loon of a grand‑da up near Kaspaterre, and the Kaspa lawyers asked me when I was passing through to deliver a message, right to Sivonie’s people at the Firelark Inn by the North Gate in Kytheu…”

“Ai ai, singer,” said Goru. “Keep on, you could spin that tale into socks.”

“Into veils and Damo-ship sails,” someone else commented from under the table, finishing with another mocking parrot-noise.

Haptin grabbed an empty tankard, banging furiously on the table. “Away, away! You’ve admired my stories and stolen my wife’s beer and insulted this fine gentleman enough today! Off with you all!”

Grumbling, the listeners wandered away. Haptin turned around, red with shame over their antics. Five Kaspa silver coins weighted the envelope on his weathered table. The stranger and his warhorse were gone. Haptin caught a glimpse of golden-yellow pelt beyond an overloaded wagon, and started to call out. The wagon moved. He saw only a lady’s little dun mare in amber silk trappings.

He pocketed the silver uncertainly and ran a finger along the ribbon‑and‑wax seal. The package was too light to contain more coin. A bank writ? He thought again about the spidery script. He wondered what Sivonie would think, inheriting money from a man none of them had ever known. Then he wondered what Madam Olvera looked like, and shook himself quickly away from that thought.

He watched a grimy hand reach up and pat around the table edges for abandoned tankards.

“Where’s your broom?” Haptin asked.

“It turned into gullfeathers and gold chains,” said the hand’s owner. “I left it to sweep sand from the sea.”

The broom leaned against a nearby wall, weathered hickory and grey-gold barley straw.

“Baid, get up.” Haptin reached for the man’s trembling hand, and the rest of him followed. A miscast spell in Baid’s youth turned a promising sorcerer into the Northgate neighborhood’s own god-touched beggar. Maraga paid him to sweep the street in front of the Firelark. He had a room in a nearby pension-house, but lurked under the Firelark’s front tables in good weather. Haptin sniffed in his direction. “How much beer did you sneak from Goru?”

“Beer, balm from the gods, brewed long before bread was baked or porridge stewed,” sang Baid. His wavering voice settled to a lower pitch. “I watched Goru watch that man with the rusty sword. Like someone he knew.” His agate‑brown eyes glittered under his unkempt blond hair. “I remember Channel Southbank. When the War spilled across the last time.”

“I know, I know,” soothed Haptin.

“Know about veils, do you? Damo warriors go shrouded to their eyes, men and women alike, to all but near-kin and friends.”

“What are you blathering about?”

“Veils,” said Baid, peering out from his splayed fingertips. “Veil-folk never quite learn to guard their faces. Open‑eyed as babes.” Then he shrugged and shambled off down the street, muttering.

Haptin forgot that comment later, when he showed the coins and parchment to his wife.

“A grand‑da? In Kaspaterre?” Maraga asked. “Our Sivvie’s family didn’t have kin left alive up Channel way. Not after the War. Lucky that her father found my sister to wed. Poor girl would’ve grown up motherless and nameless.”

Sivonie roomed in the Keep’s servant quarters that week, because of the hours needed on some important project. So Maraga took the parchment envelope and the silver up the next morning.

As inheritance, the coinage seemed little worthy of lawyers and magistrates. The unfolded envelope was blank, lacking even a message.

“A grand‑da? In Kaspaterre?” Sivonie asked, drooping. She’d been holding out for a treasure map. A magical quest out of Haptin’s tales. Possibly, an enchanted needle to bolster the little magics she’d slowly learned to sew into her work. Anything beyond Kytheu’s confines!

“I knew it,” said Maraga. “That messenger must have been a thief all along I’ll have the watch out looking for him, Sivvie, to get the rest of your money.”

#

After moonrise, Talai stood again on the highest balcony. Kytheu’s fan-shaped sprawl was evening-blue now, spangled with amber lamps and silver canals. Distinct noises lifted like air bubbles rising from underwater moss: love songs and arguments, cart-wheels bouncing on cobbles, pots clanging, dogs barking, ship’s whistles, and the hourly skirmish when two dozen merchant-family bells clanged the time with different music.

A shadow made of dark blue cloth waited until Talai moved away from the edge, before clearing its throat.

Talai pinned the shadow to a pool of torchlight, and ripped away his face‑veil. Framed in short-cut black hair, pale features grinned up at her.

“General Josen?”

“No, I’m the Old Man of the Channel, come to rescue his exiled Southbanker children,” snorted the man. “Let me up, Tai. That kraken’s hold of yours is still brutal. I’m no general anymore, and not as young as I used to be.”

“Ha,” said Talai. She grimaced as her own knees popped and cracked. “What in the ancestors’ names are you doing here?”

“Looking for you.” Josen shrugged out of his stalking mantle and smoothed out his blue silk tunic. “Unofficially.”

Talai looked at the visible part of his sword, smothering a laugh. “What is that, a strolling player’s prop? You can’t fight with it.”

“Look closer, Tai.”

“I did. It’ll lose its hilt in a strong breeze.”

“Not fit for a Queen?”

“Josen, please. The Hawk-Queen of Kytheu had some debt to my father. She helped patch me up. I didn’t know she was going to proclaim me heir! For twenty years, I’ve put on faces that I didn’t feel for these people.”

Josen leaned against the tower wall. “At least you’ve had a home these twenty years. I’ve been a freebooter. And I’ve learned something: boots aren’t free. Neither are weapons, food, a roof, and a doctor when something goes wrong. How goes the subversion of Kytheu Commonwealth’s treasury?”

Talai’s shoulders sagged. “A bad plan from the start. They can’t see past their borders. A war beyond the Channel means nothing to them.”

“Then leave.”

“I can’t!” She waved a helpless hand toward the city. “They need me. Swords are only jewelry for rich merchants, here. It took them twenty years to decide on a new Queen, they squabble so. Kytheu-folk will still be bickering when the war comes south.”

“Stay here, and you won’t stop that.”

“I owe Kytheu for hiding me until the Oracle summoned me back. He took his time about it.”

Josen shrugged. “The Old Man of the Channel’s got a lot on his mind. Would you rather command Kytheu or your rightful people? The rebels need you.”

“They’re still waiting for the young heroine to ride out of the south,” Talai said, fingers twisting a hank of her grey-streaked red hair. “Josen, she died. She died when my father fell on the battlefield and the usurper stole the Isles. She died when I woke to find myself spell-aged and weak. I’m a hag, not a warrior. There’s nothing left to rally around.”

“Not true, Tai,” Josen said. He raised one hand to caress the ugly sword in its sheath. The metal shone with a brief glow, like lightning seen many miles away. Then a different sword hung in the leather harness. Josen drew the blade.

Rusted metal became blued-steel, forged patterns rippling along the blade. The wave-sculpted hilt glowed with gems green as sunstruck jungles, blue as summer evenings.

“Oh,” said Talai, then breathlessly, “Linca’s sword! But it’s been lost for a thousand years.”

“On orders from the Old Man himself, fourteen of your father’s knights searched the coast. Six of us lived to find Mad Emperor Juka’s tomb, on one of Juka’s private islands.”

Talai raised one eyebrow. “I’ve heard about those islands. Who’s left?”

“Sir Kambel, Lady Salu, and me. But we don’t need Kytheu and its gold, now. We’ve got enough Damo treasure to bring mercenary companies and sorcerers from half the world over. Now we need our War‑Queen.”

She reached for the sword. Her hand twitched. The beautiful weapon fell, clanging on the tiles. “You’re too late. That would be a farce,” she said.

Josen retrieved the sword, held it out again. “I can give Kytheu a Queen, and our folk their Warrior.”

Talai cradled the sword, her sharp chin resting atop the hilt. “How?”

#

Sivonie brought the envelope home, along with the broken wax seal and green ribbons. Her father, barely an hour back from his barge, took one look at it and sat down hard, tears and laughter stealing his voice. He held the ribbons up to lamplight. Damo runes shadowed between the two‑layered ribbons. Sivonie’s father kissed the ribbons, then burned them to white ash in the fire-grate. “A grand‑da in Kaspaterre, indeed!” he said, head in hands.

“Sivvie, dear heart,” said her mother. “You know I’m not your birth-mother.”

Sivonie squeezed her father’s shoulder. “Yes. You adopted us.”

“I’m not your father.” said the barge captain, his big hand finding hers. “Never knew who was. Your ma was a Channel lass big with you when I found her hiding wounded in my barge. Some unpleasantness with a wreaked boat, she said. Isle soldiers hunting in the Delta. I got her back down to Kytheu. She birthed you, then died of a knife-cut that never healed. But she said this day might come. You’re meant for more than a needle.”

Breath caught in Sivonie’s throat.

“What will we tell Haptin and Maraga?” said Sivonie’s mother.

“About what?” asked Sivonie.

“Maraga?” asked Sivonie’s father. “What you choose to tell her. Your sister’s kept our secrets for years already. Haptin? Think about it.”

Sivonie’s parents shared a rueful grin. “Gods, no,” said her mother. “We’d be one of his stories inside a day.”

“Will someone please explain –” Sivonie began, as the courtyard bell clanged. Family used the kitchen entrance. Sivonie’s mother put on a green and white mantle that Sivonie had embroidered, and immediately seemed taller, prouder, a queen among merchants.

“Mother?” Sivonie asked.

Her father touched a finger to his mouth, for silence, and showed her a cubby-hole she’d never noticed. Its fitted-board back opened on a little hidden room with carefully-stocked traveling packs and torches wrapped in waxed paper. From a narrow padlocked door wafted the scent of river-mud.

“That opens under our dock. Stay here,” he started, hand going for the long knife always at his belt. Sivonie’s mother was back in the doorway.

“All’s well,” she said. “Maybe. Hiding and running won’t help, this time. The Warlord wants to see Sivonie.”

“Go,” said her father. “Talai will know how to unravel this mess.”

#

The whirlwind settled when Sivonie was escorted not to the stateroom she expected, but to the familiar cellar chapel. A dour-looking Channelman closed the door on ten council members and the majordomo. The Channelman’s palm left a silver-glowing print on the door. Faint silver fire filled the gaps between new wood and ancient stone.

“We may speak safely?” asked the woman in chain-armor and a red surcoat.

“Until they bring that door down,” said the Channelman.

Warlord Talai shook her head. “They don’t love me that well. Sivonie Firelark,” she began, turning to face the embroiderer. “I’m told you have a gift for needle and thread. That you set careful, quiet magic into your craft. Folk who wear or bear your pieces breathe easier if they are sick. Sleep better, if they are troubled. Remember kindness, when they are moved to fury.”

“I try, Your Majesty,” said Sivonie, gulping down her nervousness. So far, the Guildmistress knew, and looked the other way. If more of the nobles knew about Sivonie’s tiny magics, would they clamor more for her work? Or less?

“I’m not Queen yet,” Talai replied with a sad smile that softened her face. “I am not of this land. Your last Queen angered many in Kytheu by naming me as heir. I thought I was alone, trapped between duty to Kytheu and my own people. Sir Josen?” she turned to the Channelman guarding the door. “Will you uncover the sword again?”

“Sivonie,” she said. “We two might be kin. Give me your hand.”

Sivonie extended a trembling fist.

Talai guided Sivonie’s tingling fingertips across the gems on the hilt.

White, jagged sparks wheeled across Sivonie’s eyesight.

She heard drums, bone flutes, massed voices singing in a strange language. An image flickered into her thoughts: lines of blue-veiled, armored folk riding across a plain, under a dark sky filled with storms and lightning. Their steeds were giant deer. Azure grass rippled under steel-shod double hooves. The foremost rider held a blue-black banner glittering with three silver lightning-bolts. Under the steel helm, over indigo veiling, the eyes looking back at Sivonie’s were green as her own.

Sivonie’s sight cleared. “What did I see?”

“Channelfolk leaving their last homeland, before finding this one,” said Talai. “You saw Queen Damoa’s banner. I saw the runes of your bloodline in the blade. Your mother was a Damothani rebel, a noblewoman cursed by her brother when he learned her lover’s name. Half of Kytheu can claim a little Damo blood by now. But you are full Damo stock like me. My half-sister.”

Sivonie swallowed. She’d only wanted a treasure-map. A needle. Something beyond Kytheu. In Haptin’s tales, heroes behaved with grace. She knelt. “What do you wish of me, sister and Warlord?”

“Help me win a war,” said Talai, coaxing Sivonie upright.

“How? I can’t use a sword.” The thought terrified her. She’d never even ridden a mule, much less a war-horse!

“You made a wish for adventure and a different life, but you’re too young to bear the weight of Kytheu’s crown. In that body. And I am too damaged to fight the battles ahead. In this one.”

Sivonie looked around at the familiar, unknown statues, longest at the female weaver breathing upon a spindle. “We could trade?”

Josen nodded. “The sword’s magic can do that, too, one time for each bearer. But only one time. Damo blood in your veins makes the exchange easier.”

“I will not lie to you, my sister,” said Talai. “My body is not utterly wrecked, but it won’t be as fine a house for your mind as your own. We are diminished from what we were. Still, those of full Damothani blood may still expect two hundred years or more. Once the switch is made, it cannot be reversed. What you lose in youth, you might gain in power. The Kytheu monarch is a figurehead, at least when the monarch‑to‑be is under suspicion of being foreign. But someone reared among them might know their games. And win them over.”

“Lady Sivonie,” said Josen. “I’ve asked around, about you. Here’s a truth: a Queen who takes up craftwork to retrain her hands and soothe her nerves, might be seen merely as eccentric.”

“Or industrious,” said Talai.

“And you get another chance at being a warrior,” said Sivonie. “But would your people recognize you?”

“The sword can vouch for my soul, by blazing my name and lineage on the air for all to see. “Your body has as much royal birthright as mine. Your true mother should have been Queen of the Isles. Some of the usurper’s allies switched sides, on that fact alone.”

I know my true mother, Sivonie thought. “We can’t do it right away,” she said. Two sets of puzzled Damo eyes met hers. “I don’t know how to use a sword. Have you ever held a needle, Lady?”

“To sew up Josen’s arm, once,” said Talai.

Josen winced, unrolling his sleeve. “Don’t remind me. We did that one without rum.”

Sivonie nodded at the neatly-closed scar. “This might work.”

“You’d agree?” asked Josen.

“This is my home,” said Sivonie, remembering her parents’ silent worry. “Not the Channel I don’t remember, not some blue world under a stormy sky. My ma and da are the ones who fed me, sheltered me, and sang me Kytheu songs. From the songs I hear now, I don’t know that I have a choice.”

“You do,” said Talai. “I can take the sword north.”

Sivonie shook her head. “I’m the one who made wishes in a Damo chapel. Haptin tells a tale of the Green Parrot of Kaspaterre, which offers an iron key to lost travelers in the coastal jungles. The key may unlock either a treasure vault or an evil temple.”

Josen made an odd sound.

“But if you don’t take it, you’ll never know, will you? I will help you,” Sivonie said.

As easy as that. Throwing away her youth for a half‑sister she’d just met! Talai was only in her mid-forties. What hampered a Damo warrior could be bearable to Kytheu’s Queen. It wouldn’t be easy, later on. Sivonie had dealt with far-older relatives’ stiff joints, worn teeth, and other ailments. She might do well by Kytheu. She might even have a hundred or more years to do it.

She grinned at Talai and Josen. “A needle’s a lot lighter than a sword. Certainly lighter than that iron key.”

Josen bit back a strangled laugh. Talai glanced quizzically at him. “A green parrot and a key,” he muttered.

“A parrot,” said Talai, her eyes widening.

“It’s an old Kytheu tale,” said Sivonie.

“I opened Juka’s vault with that key,” said Josen.

“How much rum and swamp fever, beforehand?” Talai asked.

“You took the Parrot’s Key?” Sivonie shook her head. “Then you can’t set foot beyond Kytheu’s borders for seven years.”

“I need to follow Talai,” Josen growled.

“You will have seven quests in seven years. Complete them, and your seven dearest wishes will come true,” Sivonie said.

“What happens if I fail?”

“Don’t fail,” said Sivonie. “I didn’t make up the legend. You’re not the first to meet that bird.”

“Nor the last,” Talai whispered.

“Stupid bird. Stupid me, thinking the sword was the easy bit,” Josen said.

“Good,” said Talai, thumping him on the shoulder. “Stay here and learn about Kytheu folk legends for me. I never took the time. Seems these people might have as much magic as the Damo. It’s just quieter.”

“Quieter? A twenty-foot-long crocodile guarded the entrance to Juka’s hoard! Then Kambel had to stick it with an arrow, and we found out it was ensouling Juka’s vengeful spirit. The croc, not the arrow,” Josen trailed off indignantly. The two half‑sisters laughed at him, kinship clear in their wry faces. Sivonie was an inch or two the taller.

#

Five weeks later, sitting on the high terrace, Sivonie braided back her grey-streaked russet hair. Careful effort eased the tangles and knots in both hair and hands. Talai hadn’t taken care of herself, keeping her pain private from doctors and servants. Sivonie enlisted both for bitterweed tea and warm cotton gloves at night. She sparred daily with Josen and a strong bamboo staff. Her eyesight and hearing were sharper than she’d feared, her new narrow fingers more deft.

Sivonie half-considered making her own coronation robes. Impatience was impolitic, and dangerous. In ten more years, she’d be a master in her own right.

Kytheu widely approved the Warlord’s new hobby. Of course, she’d summoned the Guild’s most-gifted apprentice to help her begin it. In turn, she won the girl a Kaspaterre inheritance. She sent Kytheu’s usual oblique promises north: grain, meat, cloth, steel, and medicines. No gold, and no warriors. She displayed, at long last, a shrewd and sincere interest in Kytheu’s affairs, sitting every afternoon in Commonwealth councils. Listening and learning as she set stitches in blue-black silk.

“Are you well, Warlord…er, I mean…” Josen stopped, flustered by the young woman in the older body. Already, this new Talai had a different look. Lusher, more elegant, more aware of the slide of braided hair against a heavy silk robe. A sorceress, not a warrior. Proving, he thought, some old stories about Damothani powers accompanying the soul, not the body it occupied. Talai’s magic had been of the forthright, stand‑to‑attack variety.

If Sivonie lived through the next few political quagmires, she’d make a good Queen. Then Josen remembered that Talai had ordered him to see to it that Sivonie survived. His first Kytheu quest.

“Josen?”

“I have to learn what to call you,” he sniffed critically. “Having a foreigner as your advisor isn’t going to endear you to Kytheu.”

“Talai always had some foreign counselors. In public or private, call me Talai,” said Sivonie, looking down at her old Northgate haunts. From this distance, the Firelark’s tile roof was a tiny carnelian square. “My father knows, and my mother. They’re glad I’m not the one riding north. Haptin would love this tale. But Haptin has a mouth like a baby pelican. In snatching up just one more fish, he tends to drop three more. He couldn’t keep it secret. I always wanted to be a traveling actress or an adventurer. Now I’m an actress in my own city.”

“No less one than Talai,” Josen offered. “Our families are the price we pay for our quests.”

Sivonie smiled at him, gestured at the new project in her work-frame. Blue-black silk, silver thread, and rock-crystal beads sketched jagged lightning-bolts under her fingers. “So we’ll make new families. We get to choose this time. I’d much rather have Haptin for an uncle, than a murdering usurper.”

“Ah, you guessed. Tai didn’t want to tell you.”

The sorceress leveled a sharp look at him, and tapped the frame. “She’ll put the sword to his throat. But it will be my banner floating over his defeat.”

Movement caught her eye, an anthill commotion down at the Gate, slowed by distance and blurred by summer dust. One leather‑clad rider shot toward the north road, whooping, on a big golden mare. Sivonie on her balcony thought she heard words in the whoop, and painted the scene in her mind’s eye:

“Hang on, Sivvie!” yelled Haptin as he pelted after the young woman. “Tell me about the Queen’s sewing-lessons! Tell me about the parchment! Where are you going with that man’s mare and his shoddy sword?”

“To Kaspaterre,” the rider sang as she shook back long brown braids. “I’ve a grand‑da who left me some money!”

Permalink